Pipa: A Closer Look at the Chinese Lute

A tour featuring The Knights, a collective and shifting ensemble of friends from the chamber music scene in Brooklyn, and Wu Man, the world’s most well-known virtuoso on the pipa (sometimes called the Chinese lute) might seem unusual at first. But for brothers Eric and Colin Jacobsen, who co-founded the Knights, this type of collaboration featuring international musicians and instruments is second nature. Both Colin, who plays violin, and Eric, who conducts the group and plays cello, have also performed for years in Yo-Yo Ma’s Silk Road Project Ensemble, joining musical colleagues who hail from every stop on the Silk Road trading routes. This immersion has inspired the Jacobsens to partner frequently with friends from the ensemble, both in The Knights and their chamber quartet Brooklyn Rider.

Wu Man is one of those colleagues, and the pipa will add a fresh twist to The Knights’s repertoire at Purdue. To learn more about how the pipa sounds and is played, we invited Purdue freshman Xuezheng Peng to the Purdue Convocations office to show us her instrument. Peng, a freshman from Yentai, China, majoring in economics with a minor in theatre, thinks she is one of only a couple pipa players on campus.

The pipa is a traditional, pear-shaped Chinese instrument with a tradition over 2000 years old. As Wu Man explains in her notes, its four strings are tuned to A, D, E, and A, and although the number of frets has varied in the instrument’s history, most modern pipas have 26 frets and six ledges arranged as stops.

Part of what makes the pipa such a complex instrument is the 70 to 80 different playing techniques for both the left and right hand. In fact, the onomatopoeic name of the instrument describes the sound of two of the basic plucking techniques. The first, “pi,” is made by plucking a string with any finger, from right to left. The second, “pa,” is the sound of the thumb plucking from left to right.

To play for us, Peng first had to tape picks of tortoiseshell or plastic, which look a bit like talons, to each of her fingers.

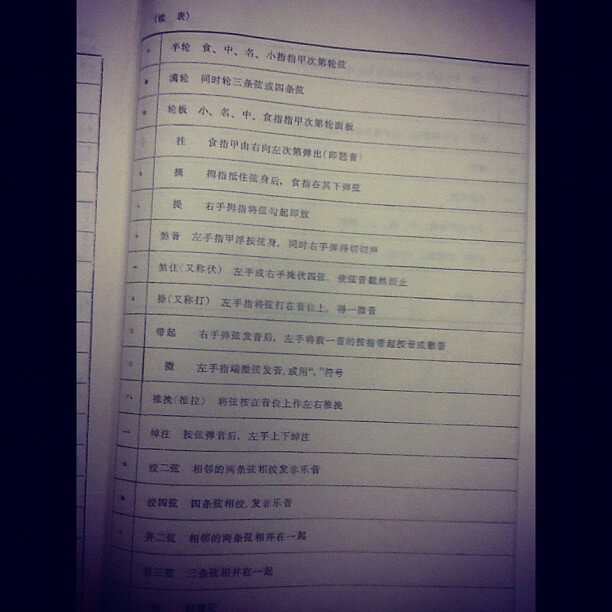

Next she opened up her songbook to select a piece, and showed us how the notation looks. The numbers designate notes, while the symbols above them indicate the plucking technique. The star symbol, for example, indicates a series where all four fingers rapidly pluck pi, followed by the thumb plucking pa, over and over again—which sounds similar to a trill or tremolo.

Some playing techniques are more common in certain styles of songs, such as sad love songs or battle songs. (Peng prefers the passion of the latter.) Thus, listeners familiar with the pipa can quickly identify the type of song being played, in much the same way that tempo and major or minor chords immediately tell us if we are listening to a march or a hymn, for example.

Peng has played the pipa for over 12 years. She started in elementary school, when four music teachers visited her school looking for promising students. They took one look at Peng’s long, slender fingers and suggested she try an instrument. Her grandfather had always played erhu, a 2-stringed Chinese spike fiddle, but Peng thought the pipa was prettier and wanted to give it a try instead. She found it very difficult at first, and it took her a long time to adjust to the size of the instrument, develop strength, and toughen up her fingers.

Peng is excited to see Wu Man perform. “Her music is really crossover. It combines Western music, Chinese music, African music—very traditional things and very modern things together. So it’s very different, very special.”

You can enjoy a sneak preview of The Knights playing Debussy’s Prelude a l’après-midi d’un faune (Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, inspired by Stéphane Mallarmé’s similarly named poem) in the gorgeous Naumburg Bandshell in Central Park. But to see how Wu Man and her pipa embellish the piece, as well as hear one of her own compositions, Blue and Green, you’ll have to see The Knights with Wu Man at Purdue Convocations on February 12.

Stacey Mickelbart, guest contributor