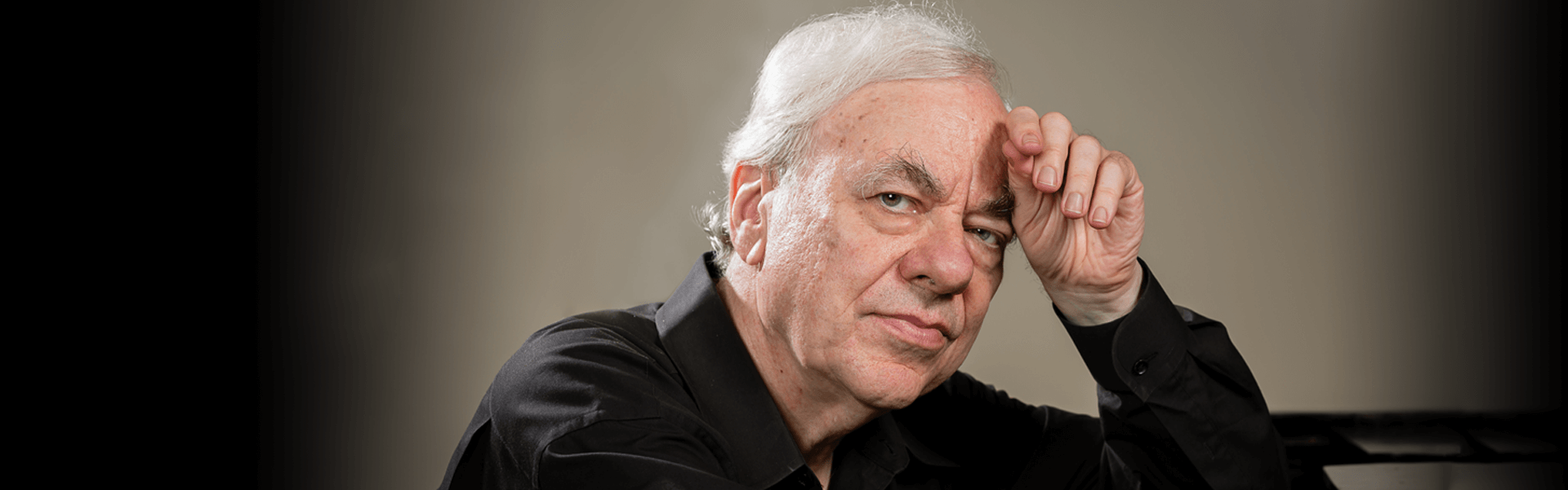

Richard Goode | Program Notes

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809)

Variations in F Minor (1793)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

March in C Major, K. 408 (1782)

Allemande in C Minor, K. 399 (1782)

Courante in E-Flat Major, K. 399 (1782)

Menuet in D Major, K. 355 (1789/90)

Gigue in G Major, K. 574 (1789)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Piano Sonata in E-Flat Major, Op. 81a (Lebewohl) (1809-10)

Das Lebewohl. Adagio – Allegro (E-Flat Major)

Abwesenheit. Andante espressivo (C Minor)

Das Wiedersehen. Vivacissimamente (E-Flat Major)

INTERMISSION

Leoš Janáček (1854-1928)

In the Mist (1912)

Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849)

Impromptu in G-flat Major, Op. 51 (1842)

Four Mazurkas

Fantaisie in F Minor, Op. 49 (1841)

Program notes by Richard Goode

Sometimes when I make a program, I’m surprised by the connections that emerge, almost as a kind of hidden theme. I didn’t plan them—but there they are!

Here, the underlying motive is darkness and light, suggested in the Haydn by the nature of the double variation form, a favorite of the composer (and of Beethoven), alternating a somber march, almost a dirge, in minor, with a graceful ornamental major counterpart. The coda, unequivocally tragic, is for me one of the most surprising in classical piano literature.

The Mozart pieces are lighter—the March is very much in the spirit of Figaro. The Allemande and Courante come from an unfinished suite in Baroque style, inspired by the composer’s newly awakened passion for Bach. The Menuet oddly combines astringent dissonance and courtly elegance. The delightful chromatic Gigue is dated May 17, 1789—Mozart probably tossed it off in an hour or so for an organist friend.

The Beethoven sonata op. 81a, known as the Lebewohl (Farewell), commemorates the return to Vienna of Archduke Rudolf, Beethoven’s beloved student and friend, who was forced to leave the city during Napoleon’s bombardment in December 1809. It is unique among the composer’s instrumental works in suggesting a clear and detailed dramatic scenario. The opening adagio presents the 3-note postern motive (Le-be-wohl) with a doleful minor cadence; the halting silences before the Allegro eloquently suggest the anxiety and unease of the leave-taking. The movement’s eventful journey ends with a striking piece of symbolism, when the distance between the two friends is mirrored in the divergence of the two voices and of the pianist’s hands, which travel to the extreme ends of the keyboard. In the middle movement, (‘Absence’), the music seems to wander about sadly, almost aimlessly, with painful reminiscences of the Lebewohl motive. The exact moment of the sighting of the returning carriage is given by a pianissimo B flat in the bass followed by a joyous outburst as the friends are reunited. The last movement, complete with ringing bells and exuberant feelings (the two friends interrupting each other in their excitement) is Beethoven at his most ‘unbuttoned’—to use his own expression.

In Janacek, the most volatile of composers, transitions from dark to light, anger to tenderness, can come in the middle of a phrase. The often jagged rhythms are inspired by those of the Czech language, carefully transcribed by the composer in his notebooks. It is a music of deep affinity with the natural world, and also of great longing and nostalgia.

In Chopin the classic and romantic sensibilities find an ideal fusion. So many worlds meet in this composer: the balance and symmetry of his revered Mozart and Bach, Polish folk modes and rhythms, above all the tradition of bel canto, translated into pianistic terms. The Fantasy, like the Haydn Variations with which the program begins, opens with a solemn march in f minor, but here the drama culminates in a radiant coda in A flat major.