Program Notes: Academy of St. Martin in the Fields with Jeremy Denk, piano

Program Notes

Academy of St. Martin in the Fields with Jeremy Denk, piano

March 24 / 7:30PM / Elliott Hall of Music

Serenade in E-flat major, Op. 6 (1892)

by Josef Suk (Křečovice, Bohemia, 1874 – Benešov, 1935)

Josef Suk was 18 years old when he composed Serenade in E-flat major, Op. 6 (1892)

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as orchestras got larger and larger and symphonies longer and longer, composers sometimes felt the need to go in the opposite direction and reduce performing forces as well as work durations. The string orchestra represented a welcome change from the full symphonic ensemble, and inspired a revival of the classical serenade-divertimento tradition, which had largely fallen into neglect during the first half of the 19th century.

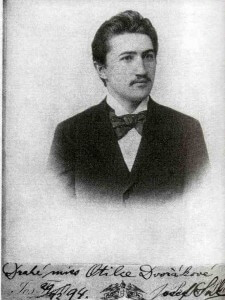

That was the tradition the eighteen-year-old Josef Suk, Dvořák’s favorite student and future son-in-law, claimed as his own in his Serenade, op. 6 (1892) which launched his career. (Dvořák’s own popular Serenade for Strings, Op. 22, which will close tonight’s concert, was written in 1875, when Suk was one year old.) Suk went on to have a distinguished career as a composer, violinist and teacher. He was a founding member of the Bohemian String Quartet and served as the director of the Prague Conservatory. One of his greatest works, his Symphony No. 2 (‟Asrael”), was written after the premature death of his wife Otilie (Dvořák’s daughter). Their young son, also named Josef, became the father of the famous violinist Josef Suk III (1929-2011).

Dvořák’s influence on Josef Suk I’s Serenade is evident at every turn; yet the young man had a different temperament, and was drawn to darker emotions. Dvořák sensed this when he told Suk to write “something cheerful for a change.” This Serenade is certainly not cheerful all the way; its longest movement is an Adagio, standing in third place, whose lyrical opening cello melody soon develops an emotional intensity not often encountered in serenades. This movement is preceded by a nostalgic “Andante con moto,” not an Allegro as one might expect and a second movement that begins as a gentle waltz yet contains an unexpected, if brief, dramatic outburst in the middle. Even the closing ‟Allegro giocoso” has its serious moments, recalling the nostalgic opening theme of the first movement before finally settling into the happy mood Dr. Dvořák had ordered.

Keyboard Concerto No. 2 in E major, BWV 1053

Keyboard Concerto No. 4 in A major, BWV 1055

by Johann Sebastian Bach (Eisenach, 1685 – Leipzig, 1750)

Café Zimmermann in Leipzig, the backdrop of Bach’s secular cantatas

As far as we know, J. S. Bach was the first composer to write concertos for a keyboard instrument. Before him, many concertos were written for strings or winds, but the harpsichord had been relegated to the role of Cinderella: always present, its role was merely to provide harmonic support as a member of the continuo group. All that changed in the 1730s, when Bach took over the direction of the Leipzig Collegium Musicum, a concert series started many years earlier by his colleague Georg Philipp Telemann. At these concerts, which took place at Zimmermann’s coffee house in Leipzig, Bach performed as keyboard soloist and also wished to feature his two grown sons, Wilhelm Friedemann and Carl Philipp Emanuel, both accomplished harpsichordists. In addition to seven concertos for one harpsichord, there are also three for two harpsichords, two for three harpsichords, and even one for four harpsichords (the latter based on a work by Vivaldi). The solo concertos are all arrangements of works originally written for other instruments, although the originals are known for only three out of seven—the early versions of the other concertos are lost.

The Concerto in E major (BWV 1053) is thought to be the transcription of a now-lost oboe concerto. Bach also recycled the same music in two of his church cantatas: the first two movements in No. 169, and third in No. 49 (both written in 1731). It is the longest of the concertos, and structurally the most forward-looking one. The most adventurous modulations and motivic transformations occur towards the middle of the movement, and the return to the home key is set of by a single measure of Adagio. These features create the impression of what would later evolve into a development section and a recapitulation, foreshadowing the sonata forms of the classical era.

The slow movement is an almost romantically lyrical siciliano (a favorite Baroque aria type) in the rarely used key of C-sharp minor. The string orchestra begins the melody as the soloist plays an accompaniment made up of broken chords—a truly ‟proto-Romantic” feature. The soloist then takes over the melody, only to return it to the orchestra at the end of the movement.

The final Allegro is one of Bach’s most virtuosic concerto movements, with a solo part that frequently and unpredictably alternates between fast sixteenth-notes and even faster sixteenth-triplets. Once again, the musical material is developed at considerable length and is subjected to rather subtle transformations.

A thorough examination of the Concerto in A major (BWV 1055) led scholars to the assumption that this work was originally a concerto for the oboe d’amore, the lower-pitched cousin of the oboe. It is a relatively brief and compact work. The first movement is based on a single rhythmic motive that is heard almost without interruption. The second movement is a lavishly ornamented aria, in siciliano rhythm as in the previous concerto, over a chromatically descending bass line that served as the basis of countless sets of variations during the Baroque era. Finally, the third movement surprises us with a cascade of thirty-second notes in the solo keyboard while the accompaniment maintains a steady dance rhythm. The thirty-seconds later alternate with slightly slower sixteenth-triplets; thus, the music moves back and forth between two different speeds, constantly challenging the performer and delighting the listener.

Serenade for Strings in E major, Op. 22 (1875)

by Antonín Dvořák (Nelahozeves, Bohemia, 1841 – Prague, 1904)

Like most composers in the early stages of their careers, the young Antonín Dvořák was struggling to make ends meet. From 1862 to 1871, he was principal violist at the new Provisional Theatre in Prague; he also taught music privately. In 1874, when he applied for the newly instituted Austrian State Stipendium for young artists, his file read: ‟Anton DWORAK of Prague, 33 years old, music teacher, completely without means.”

By this time, Dvořák was already married and the father of an infant boy; thus he had much at stake in this competition. Fortunately for him, the selection committee, whose members were conductor Johann Herbeck, music critic Eduard Hanslick, and Brahms, decided in his favor. As the report stated:

He has submitted 15 compositions, among them symphonies and overtures for full orchestra which display an undoubted talent, but in a way which as yet remains formless and unbridled….The fact that Dvořák’s choral and orchestral compositions have been performed frequently at big public concerts made a favorable impression. The applicant, who has never yet been able to acquire a piano of his own, deserves a grant to ease his straitened circumstances and free him from anxiety in his creative work.

Dvořák won an award of 400 gulden; in addition, he had attracted the attention of some of the greatest musical luminaries in the Monarchy’s capital. The young composer had made his first step towards fame and recognition.

Buoyed by his success, Dvořák launched into a series of new projects. During the spring and summer of 1875, he finished three chamber works, a song cycle, a symphony (No. 5), and the Serenade for Strings, an impressive output that reflects the composer’s new-found confidence.

In the five-movement Serenade, Dvořák demonstrated the high level of compositional virtuosity he had attained by his early thirties. Using simple forms (four of the five movements follow plain A-B-A structures with contrasting middle sections followed by a return of the opening material), he nevertheless achieved considerable melodic and harmonic variety.

The Moderato first movement has a short legato theme with a range of only four notes, using imitation, followed by a second theme that has no imitation, and is introduced by a very audible jump into a new, and not closely related, key.

The charming opening theme of the second-movement Tempo di Valse is built of asymmetrical five-bar phrases, but is fairly simple harmonically. Conversely, the movement’s Trio, which is no less attractive melodically, has regular four-bar phrases but contains some highly unusual modulations.

Imitative techniques reappear in the lively Scherzo; the central Trio section has broader phrases and slower note-values, though the composer insisted that it must be played ‟in tempo” (that is, the beat remains the same). The ending of this movement is especially beautiful as both the Scherzo and the Trio themes are recalled as if in a dream, cut short by a sudden return to the more agitated tone of the beginning.

The fourth-movement Larghetto presents a lyrical, harmonically stable opening melody and a more rhythmical and constantly modulating middle section. The concluding movement, the only one in sonata form, is the most complex of the five. Starting ‟off-key” (not in the main tonality which it only reaches later on), it has a normal exposition with three themes and a regular recapitulation, but no real development. Instead, there is a short and quite unusual middle section. After a few measure of suspense in which the first violins repeat two notes in highly unpredictable rhythmic patterns, the cellos surprise us with a replay of the Larghetto melody (fourth movement). The recapitulation is followed by a return of the first movement’s opening. A brief Presto coda, combining the first and third themes of the Finale, closes this remarkable work.

Notes by Peter Laki

Visiting Associate Professor, Bard College